Cherubini - Médée, at the Opéra Comique in Paris

Opéra Comique, Paris, Monday February 10 2025

Conductor: Laurence Equilbey. Production and Video: Marie-Ève Signeyrole. Sets: Fabien Teigné. Costumes: Yashi. Lighting: Philippe Berthomé. Médée: Joyce El-Khoury. Jason: Julien Behr. Créon: Edwin Crossley-Mercer. Dircé: Lila Dufy. Néris: Marie-Andrée Bouchard-Lesieur. Première suivante de Dircé: Michèle Bréant. Deuxième suivante de Dircé: Fanny Soyer. Actress: Caroline Frossard. Extras: Inès Dhahbi, Sira Lenoble N' Diaye, Lisa Razniewski, Mirabela Vian. Maîtrise Populaire de l'Opéra-Comique. Accentus chorus. Insula orchestra.

|

| Photos: Stefan Brion |

Cherubini’s Médée was first performed in 1797 at the Théâtre Feydeau in Paris, of which he was the director. Under Napoleon, the Feydeau and Favart troupes were merged to create the Opéra Comique. So we might say this production is a homecoming, especially as it follows the 2008 critical edition used by Christophe Rousset in Krzysztof Warlikowski’s staging, which I saw in both Brussels and Paris. Franz Lachner’s 1850s recitatives are eliminated and the spoken text restored, in line with the opéra comique format. Whether or not that actually makes an opéra comique of Médée, or rather a hybrid of some sort was, even in reviews after the premiere, open to question. For La Décade philosophique, littéraire et politique, a paper founded in 1794, for example, it was: ‘... neither comedy, drama, tragedy, comic opera nor grand opera. It is a mixture of sung and spoken tragedy, rather disparate for true friends of the art, but which, it is said, will become established, since the public welcomes it.’ On the title page of the score, spoken dialogues or not, it is simply an ‘opéra’.

Apart from two of the principals’ being announced sick (more of that later), the main problem with this new Médée is, to my mind, a familiar one: directorial overload. Marie-Ève Signeyrole (assisted by her dramaturge) focuses on two main themes. I have abridged, but not otherwise altered, the following quotes, taken from an interview on the house website:

‘The first thing that interested us was how we could deal with the question of the foreigner, the stranger and the monster. This woman has left everything, her country, her homeland, her family, her customs, her culture, her religion, and finds herself a stranger in a land of asylum that repudiates her.’

Next: ‘Generally, it is in the desire to kill themselves that (women in prison for infanticide) kill their children. When you talk to them, you realise they were all victims of domestic violence or incest in their childhood. They are part of a cycle of violence that they will ultimately perpetuate. In this version of Medea, we give her a contemporary counterpart (an actress), in prison for life. The children are both the children of this woman in prison and Medea's. They are the link between the two.’

And so: ‘What if Medea were the product of a racist, patriarchal society?’

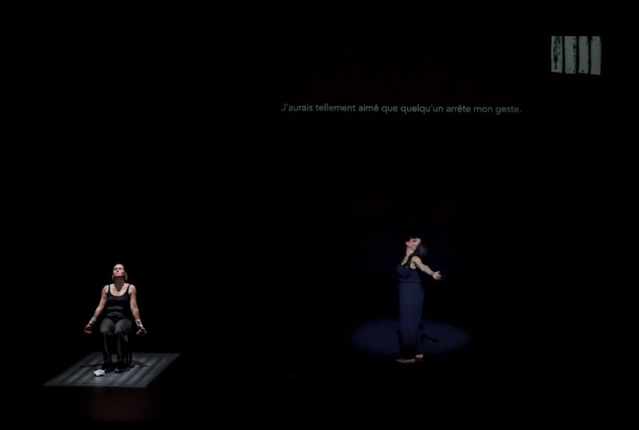

Already, with the actress and the children (albeit the most convincing, most engagingly natural child actors I’ve ever seen) on stage nearly all the time, we can see overload looming. Those who hate action during overtures would go bananas. Even before the orchestra strikes up, in silence broken only by curious sound effects, we encounter the black-walled prison cell with its barred window, and the actress, her wrists grubbily bandaged. Soon, she’s joined by Jason and the kids, on a pretend sailing ship, and there’s video of a choppy sea, its water turning red, and even spoken text, not from the libretto, during the music. The actress, sitting or standing, doing nothing, grafted-on extras and action, filmed and live video, sound effects, spoken and projected texts, an interpolated nursery rhyme, and a clutter of furniture and props, are almost constant features of the first two acts, an over-busy amalgam that makes it hard, at times, to keep up.

In act one, the women’s chorus are seamstresses bustling to finish near-naked Dircé’s wedding dress, on a catwalk of big, black tables pushed together diagonally across the stage. As the Argonauts arrive, the tables are rearranged, banquet-style with chairs and candelabras, cluttering the stage more than need be and forcing the chorus to squeeze in around them. The costumes, anticipating the wedding, are contemporary party-wear, with fancy millinery for the women, though one wears a 20s flapper dress, as if thoroughly modern Millie strayed in from another theatre by mistake. Oddly, considering the designer has worked for Bob Wilson, these costumes aren’t especially well-cut or smart. As a result, Créon’s court has an unexpectedly tacky, low-budget look, not improved by the greige double-breasted coat and trousers he wears throughout. Dircé now has an off-the-shoulder white dress; Jason is dressed as a groom but, a serial womaniser as well as a chain-smoker and child beater (he slaps his son loudly for his boisterousness), sings his love not to his bride but while flirting with one of the guests. Médée arrives in an exotic caftan, with heavy oriental jewellery and a tattooed chin, to mark her outsider status. We never actually see the golden fleece, but the briefcase it’s carried in glows with golden light every time it’s opened.

Act two finds Médée and her companions pegging out washing on a giant spider’s web at the rear. Interesting detail: Médée holds a little garment to her nose. In Euripides, at one point she recalls the smell of her children’s soft skin. I wondered if the director was thinking of that. While Créon dialogues with her, ending up somehow with his head cradled in her lap, his men, in black, drag Néris and the others off to beat and rape them. Jason arrives in his shirtsleeves, drunk, flask in hand. Médée starts dipping white roses in poison and weaving the fatal wreath.

I was so exasperated by the production so far that I considered leaving at the interval (placed lopsidedly after acts one and two). But as act three would only be an extra half-hour, I stayed. When I do leave at the interval, people usually tell me it got better after; so it did this time, with simpler sets and less of the manichaean, me-too tub-thumping. Two of the tables are now in the centre of a simple set. On them, the actress on one side and Médée, now in black, on the other set out the kids’ breakfast: cornflakes and milk, the latter in close-up, for some reason, on video at the rear. In what seemed to me quite a clever bit of business, even comic relief, Médée’s tergiversations over the children’s fate are treated as a mock duel between her and her laughing kids (rather as a modern mum might say ‘You’re so cute I could eat you’), she wielding a breakfast baguette, her son his spoon. When the time comes actually to do the deed, the set has been simplified to just a white curtain against the black background, and a sheet and two pillows are enough to symbolise the victims, thankfully no longer present.

As I mentioned above, after the audience had settled in, the baleful man-with-a-mike, as familiar to opera-goers as the ubiquitous bravo guy, stepped out to make an announcement. Both Dircé (Lila Dufy) and Médée (Joyce El-Khoury) were sick, but had agreed to soldier on. Not a promising start, and Lila Dufy was clearly affected. I’d guess she has quite a rich, ductile voice, but in the circumstances she was understandably cautious, thinning at what is probably usually a sweet top, and her diction was cloudy (unusually good diction was otherwise, as my neighbour remarked, a striking feature of the whole evening). Marie-Andrée Bouchard-Lesieur, on the other hand, was evidently in the best of health. New to me, she combines a fluid, golden mezzo voice with equally radiant stage presence.

In this production, Jason is such an unpleasant character that it was almost hard to assess his singing fairly. Julien Behr is a tenor whose voice, when I first saw him in Hahn’s Ciboulette, over ten years ago, I already found ‘young, sweet and pretty.’ Now that his career has reached the stage where his portrait fills the cover of the current issue of Opéra Magazine, his voice is stronger and naturally more mature, and he has the dramatic temperament and ideal weight for Jason. The directing left him, however, no room for charm, physical or vocal. Edwin Crossley-Mercer has also, equally naturally, matured, in his case gaining a certain rondeur and velvety plumminess, without impairing his diction. His phrasing rings as true as ever. He looked, however, vaguely uncomfortable in the role as directed by Marie-Ève Signeyrole, trussed up in his frock coat and rolling his eyes like a silent-film villain.

Joyce El-Khoury relied on her experience, vocal technique and dramatic abilities to carry her through. These ubiquitous post-covid coughs and colds play havoc with anyone’s breathing, so of course there were times when it was hard for her to sustain a note in the medium, and she had to use all her skills to ‘cheat’ her way artfully through the top notes. But what a success she made of it, in the circumstances. I could only imagine what we’d missed. She was loudly applauded and cheered.

Laurence Equilbey’s conducting was fortunately more vigorous than for her flaccid Freischütz at the TCE in 2019. ‘Weber should zing, not slouch,’ I wrote at the time. Here, Cherubini zinged. However… I ventured, when reporting on the recent Castor et Pollux under Currentzis, to write that ‘as far as I know, it’s a virtuoso ensemble but not a “HIP” one.’ I was taken to task for that by a lady from Russia: ‘Currentzis is literally practicing HIP like since 2004.’ Not wanting to initiate a fruitless debate, I didn’t ask her how she squared that with the cimbalom in the pit. But anyway, concerning Equilbey’s Insula orchestra, my thought this time was ‘it’s a “HIP” ensemble, but not a virtuoso one.’ I don’t understand how press critics can claim, as I’ve read, that Insula attains technical perfection. While the conductor remains focused on the singers and stage, giving the orchestra fewer cues than they need, they profer staggered attacks, dubious tuning, undisciplined cross-rhythms, chaotic cadences in accompanied recitatives (OK, it’s tricky to navigate together through a twiddly fioritura and still ‘land’ in time with the singer on stage, but Equilbey should have given them more help) and obbligato solos unworthy of a major house. This sounded like amateurism to me.

And while Laurence Equilbey is highly praised for creating the Accentus chorus, I’m not sure they’re cut out for opera - though they do a lot of it, including, last year, Aida. Like walking and chewing gum, they seem to find it hard to sing and act at the same time and were occasionally, in the heat of the action on the crowded stage, shambolic.

Note: an edited version of this post may be published on Parterre.com.

Comments

Post a Comment