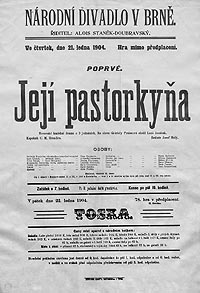

Janacek - Jenufa

Hungarian National Opera, Budapest, Saturday April 18 2015

Conductor: Graeme Jenkins. Production: Attila Vidnyánszky. Sets and costumes: Olexander Bizolub. Buryja: Éva Balatoni. Laca Klemen: János Bándi. Steva Burya: Atilla Kiss B. Kostelnicka: Gyöngyi Lukács. Jenufa: Szilvia Rálik. Mill Foreman: Gábor Bretz. Mayor: László Szvétek. Mayor's wife: Katalin Gémes. Karolka: Krisztina Simon. Neighbour: Éva Várhelyi. Barena: Erika Markovics. Jano: Eszter Zavaros.

Conductor: Graeme Jenkins. Production: Attila Vidnyánszky. Sets and costumes: Olexander Bizolub. Buryja: Éva Balatoni. Laca Klemen: János Bándi. Steva Burya: Atilla Kiss B. Kostelnicka: Gyöngyi Lukács. Jenufa: Szilvia Rálik. Mill Foreman: Gábor Bretz. Mayor: László Szvétek. Mayor's wife: Katalin Gémes. Karolka: Krisztina Simon. Neighbour: Éva Várhelyi. Barena: Erika Markovics. Jano: Eszter Zavaros.

|

| Photo: Attila Nagy |

For a start, the two tenors had a problem with pacing. Vocally they were sharply contrasted: Attila Kiss B.'s voice is clear and brassy; János Bándi's is darker and, in timbre but not volume, softer. Both threw themselves almost alarmingly into the first act, and this time Kiss B. was in better act-one form than as Calaf in January. But by act two he was already strained, and János Bándi, though globally an admirable Laca, was audibly tired by act three.

I'd thought, again in January, that Szilvia Rálik would be better cast as Jenufa than as Turandot. She produced some great notes on Saturday night, and there were undoubtedly "moments", but for Jenufa, at the top her voice is in fact relatively hard, sometimes strident, and at the bottom, relatively weak, i.e. some of the role sits low for her. Also, her stage presence is more regal than young and innocent. So, though she is a local star and features in close-up on posters around the city, she was overshadowed somewhat by Gyöngyi Lukács as Kostelnicka: vocally expressive, not too chesty, acting sometime quite violently, but visually too young (Jenufa could have been her elder sister) and with an almost completely expressionless face. Gyöngyi Lukács got a bouquet flung at her; Szilvia Rálik not, which was embarrassing.

Everyone, soloists and chorus, had their eyes glued on the conductor and/or prompter, and chorus movements seemed clunky (occasionally cramping the the vigorous folk-dancers) and unsure, like the singing, which was hesitant and, for such large numbers, oddly faint-hearted. As was the orchestra, disappointingly bland and undramatic under Graeme Jenkins. Surely in Janacek the orchestra should be a genuine protagonist and have more impact and oomph.

The production was simple. It would be nice to say simple and effective, but it was really more simple but, on Saturday at any rate, disjointed. The act-one set had a large mill wheel at the back towards the left, and an all-purpose door to each side at the front. For act two, the wheel stayed in place, but to create the more intimate space needed, large nets were hauled up, interwoven with rags, and some basic furniture was brought on. In act three, the mill wheel had gone but there was a smaller one set up in the air to make a maypole, and a long table was placed diagonally across the raked floor.

The "idea" introduced at this point was not very convincing: extras brought on two-foot cubes of plastic ice and started piling them up. Once the baby had been found, a fourth block arrived wrapped in sacking. When this was pulled off it revealed not, fortunately, the baby with its red cap, but an angel figurine, complete with burning candle (yes: inside the ice). A miracle, I suppose it was meant to be.

Overall, the staging seemed, as I said above, clunky (including the lighting) and under-prepared. The costumes, however (unlike the sets, though by the same designer) were very interesting. I don't know anything about Moravian folk dress, except that it is lavish; so I don't know if, in the inter-war period (which we could guess at from some chorus members in simple blouses and knee-length skirts), there were really 1930s variations on the folk theme, or if the idea of having smocked or embroidered and fringed or beribboned patches on the men's modern suits, for example, was the designer's. Whatever, this was a rare case of the costumes stealing the show from the sets or the production overall.

|

| Bartok |

Maestro Wenarto sings the opening of Jenufa.

Comments

Post a Comment