Saint-Saëns - Samson et Dalila

ONP Bastille, Monday October 24 2016

Conductor: Philippe Jordan. Production: Damiano Michieletto. Sets: Paolo Fantin. Costumes: Carla Teti. Lighting: Alessandro Carletti. Dalila: Anita Rachvelishvili. Samson: Aleksandrs Antonenko. Le Grand Prêtre de Dagon: Egils Silins. Abimélech: Nicolas Testé. Un vieillard hébreu: Nicolas Cavallier. Un Messager philistin: John Bernard. Premier Philistin: Luca Sannai. Deuxième Philistin: Jian-Hong Zhao. Orchestra and Chorus of the Opéra National de Paris.

Just as I was happy to hear Verdi’s Requiem again last week, I was happy to hear Samson et Dalila again this Monday. Saint-Saëns is unfashionable and underrated, but I like him a lot, and wonder not just why I’ve never seen Samson staged before, but why we don’t get at least some of his other operas.

Musically, it was a rare treat. After what I briefly thought was a rather ponderous, Brahmsian start, bringing to mind the Requiem (Brahms’s, not Verdi’s) and raising initial fears, Philippe Jordan crafted a surprisingly intimate, lovingly shaped and sculpted performance, a model of the clarity and elegance the French see as their peculiar talent. The orchestra was on its best behaviour and the chorus was at its most impressive, as you might expect in this work.

So the fundamentals were excellent. In addition, our two principals were surely among the best you could hope to hear (though I did read criticism of their “un-French” style - too technical a point for me: I was just happy to have them, true French style or not). Aleksandrs Antonenko has a powerful, dramatic tenor voice. He made up in vocal heft for relatively uncharismatic stage presence in the first two acts. Then, after bringing down the act 2 curtain with a ringing “Trahison!”, in act 3 he acted up a storm, vocally (including some of those howling, Russian-style “wounded bear” sounds) and physically.

Anita Rachvelishvili is a special case. I don’t know if there’s a name for the phenomenon (perhaps I should call it a gift) that allows some (very few) singers to reach every corner of a large house while singing very softly. Pavarotti could do it. I mentioned above the intimacy of Philippe Jordan’s conducting. Rachvelishvili has a big, richly-timbred voice - a great bronze bell - but astonishingly sang “Printemps qui commence” in the softest, most delicate, tender and intimate way throughout – with even the lowest notes clearly audible and in tune: in other words, conjuring up boudoir-intimacy in the black hole of the Bastille. Later in the evening, of course, she let rip impressively - as well as being dramatically committed. In other words, she was fantastic. My fear now is that the Met (where she was already Carmen to Antonenko’s Don José in 2014; my guess is Samson et D. suits them both better) will sink its claws into her and we’ll never see her here again. Let’s hope she hates flying.

Not much to say about other cast members, except that it was a shame Nicolas Cavallier wasn't around at the end to take a bow. I'd have clapped loudly.

The production wasn’t, I thought, up to the same standard as the music. Having heard it was updated, I was surprised to hear a colleague who saw it before me say it was “conventional,” but I now see what he meant: the familiar “repressive regime” approach, with extras in black jumpsuits, baseball caps and sunglasses waving machine guns and a dictator (in this case, the High Priest) in a suit with a pistol playing Russian roulette with his captives - Hebrews in drab, dirty, wartime rags.

The set was basically the same throughout. The sides and rear of the stage were faced with square, slate-grey slabs. A wide, Mies-van-der-Rohe style “aquarium”, with creamy net curtains all round, was raised on piers, with a tunnel beneath, in act 1, so the Philistines could keep an eye on the Hebrews. In act 2, it was on the ground and contained Delila’s bedroom, furnished with sleek, peachy-coloured art-deco armchairs on a powder blue carpet, a bed and an oval, full-length mirror. In act 3 it was raised again, but the furniture had gone bling-bling for the bacchanalia: ornate gilt frames and crimson crushed velvet… and the facing slabs had turned gold.

The key directorial ideas were plausible enough: Samson so smitten by Delila he cuts his own hair off and hands it to her; Delila so out of sympathy with the Philistines and full of remorse she douses the place and herself with petrol before handing Samson a lighter. In the updated setting, I wondered how the director would deal with the ballets (supposing he didn’t just give up and ask for them to be ditched, as some do). In act 1, devilish, gold painted dancers performed a vision in which Samson foresaw his eyes gouged out. In act 3, as the ballet music struck up, racks of gaudy oriental costumes were bustled in and the High Priest’s guests stepped out of their evening dresses and dinner suits to change for a fancy-dress orgy. This was quite clever. The act 1 devils were back among the guests, drinking from bottles, whipping and spitting on Samson. Throughout the work, Delila had expressed doubt and misgivings at her role. At the end, as I said, she took a jerry-can, doused the place and herself with petrol and handed Samson a lighter. The ensuing explosion was spectacular, with gold plaques popping off the wall (unfortunately but I suppose unintentionally recalling the problems the Bastille has had with its square facing slabs, held back by nets from falling on passers-by) and dazzling yellow lights shining through in our faces.

As I say, there were some clever ideas. But to me the first two acts, being so like so many productions we see these days, lacked specific “personality” – they could have been from any modern version of almost any opera. And while my companions were quite happy with act 3, I usually find simulated lasciviousness, same-sex groping and jiving to the score ultimately unconvincing. So, “conventional” was about right. To be honest, like the old ladies we chatted to at the interval, I think I might have been quite happy to have a “period” staging for a change.

Wenarto: a different version of "Printemps qui commence".

Conductor: Philippe Jordan. Production: Damiano Michieletto. Sets: Paolo Fantin. Costumes: Carla Teti. Lighting: Alessandro Carletti. Dalila: Anita Rachvelishvili. Samson: Aleksandrs Antonenko. Le Grand Prêtre de Dagon: Egils Silins. Abimélech: Nicolas Testé. Un vieillard hébreu: Nicolas Cavallier. Un Messager philistin: John Bernard. Premier Philistin: Luca Sannai. Deuxième Philistin: Jian-Hong Zhao. Orchestra and Chorus of the Opéra National de Paris.

Just as I was happy to hear Verdi’s Requiem again last week, I was happy to hear Samson et Dalila again this Monday. Saint-Saëns is unfashionable and underrated, but I like him a lot, and wonder not just why I’ve never seen Samson staged before, but why we don’t get at least some of his other operas.

|

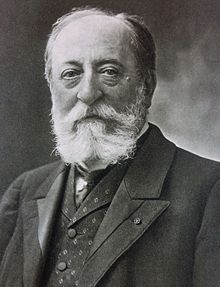

| Saint-Saëns |

So the fundamentals were excellent. In addition, our two principals were surely among the best you could hope to hear (though I did read criticism of their “un-French” style - too technical a point for me: I was just happy to have them, true French style or not). Aleksandrs Antonenko has a powerful, dramatic tenor voice. He made up in vocal heft for relatively uncharismatic stage presence in the first two acts. Then, after bringing down the act 2 curtain with a ringing “Trahison!”, in act 3 he acted up a storm, vocally (including some of those howling, Russian-style “wounded bear” sounds) and physically.

Anita Rachvelishvili is a special case. I don’t know if there’s a name for the phenomenon (perhaps I should call it a gift) that allows some (very few) singers to reach every corner of a large house while singing very softly. Pavarotti could do it. I mentioned above the intimacy of Philippe Jordan’s conducting. Rachvelishvili has a big, richly-timbred voice - a great bronze bell - but astonishingly sang “Printemps qui commence” in the softest, most delicate, tender and intimate way throughout – with even the lowest notes clearly audible and in tune: in other words, conjuring up boudoir-intimacy in the black hole of the Bastille. Later in the evening, of course, she let rip impressively - as well as being dramatically committed. In other words, she was fantastic. My fear now is that the Met (where she was already Carmen to Antonenko’s Don José in 2014; my guess is Samson et D. suits them both better) will sink its claws into her and we’ll never see her here again. Let’s hope she hates flying.

Not much to say about other cast members, except that it was a shame Nicolas Cavallier wasn't around at the end to take a bow. I'd have clapped loudly.

The production wasn’t, I thought, up to the same standard as the music. Having heard it was updated, I was surprised to hear a colleague who saw it before me say it was “conventional,” but I now see what he meant: the familiar “repressive regime” approach, with extras in black jumpsuits, baseball caps and sunglasses waving machine guns and a dictator (in this case, the High Priest) in a suit with a pistol playing Russian roulette with his captives - Hebrews in drab, dirty, wartime rags.

The set was basically the same throughout. The sides and rear of the stage were faced with square, slate-grey slabs. A wide, Mies-van-der-Rohe style “aquarium”, with creamy net curtains all round, was raised on piers, with a tunnel beneath, in act 1, so the Philistines could keep an eye on the Hebrews. In act 2, it was on the ground and contained Delila’s bedroom, furnished with sleek, peachy-coloured art-deco armchairs on a powder blue carpet, a bed and an oval, full-length mirror. In act 3 it was raised again, but the furniture had gone bling-bling for the bacchanalia: ornate gilt frames and crimson crushed velvet… and the facing slabs had turned gold.

The key directorial ideas were plausible enough: Samson so smitten by Delila he cuts his own hair off and hands it to her; Delila so out of sympathy with the Philistines and full of remorse she douses the place and herself with petrol before handing Samson a lighter. In the updated setting, I wondered how the director would deal with the ballets (supposing he didn’t just give up and ask for them to be ditched, as some do). In act 1, devilish, gold painted dancers performed a vision in which Samson foresaw his eyes gouged out. In act 3, as the ballet music struck up, racks of gaudy oriental costumes were bustled in and the High Priest’s guests stepped out of their evening dresses and dinner suits to change for a fancy-dress orgy. This was quite clever. The act 1 devils were back among the guests, drinking from bottles, whipping and spitting on Samson. Throughout the work, Delila had expressed doubt and misgivings at her role. At the end, as I said, she took a jerry-can, doused the place and herself with petrol and handed Samson a lighter. The ensuing explosion was spectacular, with gold plaques popping off the wall (unfortunately but I suppose unintentionally recalling the problems the Bastille has had with its square facing slabs, held back by nets from falling on passers-by) and dazzling yellow lights shining through in our faces.

As I say, there were some clever ideas. But to me the first two acts, being so like so many productions we see these days, lacked specific “personality” – they could have been from any modern version of almost any opera. And while my companions were quite happy with act 3, I usually find simulated lasciviousness, same-sex groping and jiving to the score ultimately unconvincing. So, “conventional” was about right. To be honest, like the old ladies we chatted to at the interval, I think I might have been quite happy to have a “period” staging for a change.

Wenarto: a different version of "Printemps qui commence".

La Rachvelishvili has been a known quantity at the Met since 2011, primarily as you note for her Carmen. I'm sure she'll be back but she does seem more connected to Europe.

ReplyDelete